PWE Forward Units

Note by Lieutenant-Colonel Johnstone for Colonel Lethbridge

SECRET

PWE Forward UNITS

Note by Lieutenant-Colonel Johnstone for Colonel Lethbridge

Origin: The idea of ‘frontline propaganda’ is nothing new in warfare: in the present war, to go no further back, it was extensively employed on both sides in France during 1939-40. Political warfare in the field on the other hand, is a conception of rather wider scope and more recent date. Apart from the attachment of one officer and one NCO to the Madagascar expedition, the first attempt to practise political warfare with a striking force was made in North Africa, under the auspices of PWE in November, 1942. Some thirty British officers (after a hasty training at PWE Country HQ) and a lesser number of Americans (mostly civilians) were attached to the expeditionary force, and of these about half went with the assault forces to Algiers and Oran. Three officers, of whom I was one, landed with the first troops (6th Commando) on the coast near Algiers, with the object of assisting the leading units on first contact with the French if the latter showed any disposition to parley. We accompanied the British and American troops during the fighting which followed between the landing and the armistice. Subsequently, under orders of Allied Force Headquarters, we took over the Algiers radio and the censorship of the local press, and, as the rest of the team arrived, built up what we should now call a Sub-Mission. Ten days after landing, Colonel Hazeltine (US Army) arrived to take command. I became his second-in-command and with the arrival of fresh American personnel (mostly civilian) the team became an ‘integrated’ Anglo-American occupational unit [Psychological Warfare Branch].

2. One of the officers in the original landing (Captain Lieven) continued with 6th Commando into Tunisia until wounded: he was the first political warfare officer to be permanently attached to a forward fighting unit and was subsequently decorated for gallantry in the field.

3. It was not until December 1942 that things were sufficiently settled in Algiers to allow of closer attention to the forward area. Colonel Hazeltine then sent me into Tunisia to organise political warfare with First Army. About the same time Captain O’Neill, formerly an officer of PWE London, but then a G3 “I” at AFHQ, got himself attached to Corps HQ and, by arrangement with PWB started on his experiments in propaganda to the enemy. He was the originator, in its modern form, of the leaflet shell, though his actual design has since been improved upon. His skill in German propaganda is probably unrivalled. The skeleton frontline unit then sketched out (there were not officers enough to complete it and practically no Other Ranks) was based from the first on integration with the Army organisation. Later, owing to the increasing predominance of civilians in the American team, and to personal reasons, this arrangement had to be modified; the difference between the British and American conceptions and organisation of frontline political warfare are touched on below.

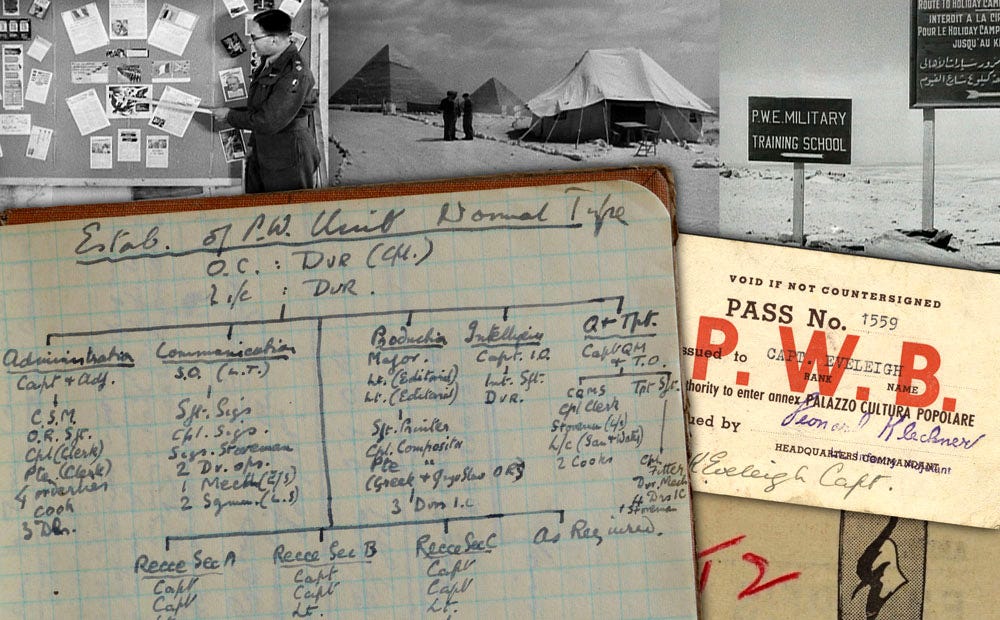

4. I left North Africa in January 1943 and went to PWE headquarters in London, where I worked on the organisation of frontline political warfare units, with particular reference to the Balkans. Clearly the first necessity was to train officers for work in such units, since, although it was relatively easy to find men already well acquainted with the French language and mentality, no such supply was available for Balkan work. After long delay War Office authority was obtained for the setting up of a Political Warfare School in the Middle East, and in April 1943 I was sent out to help in establishing it. The School opened on June 21st, 1943, the first War Establishment for a Field Unit (Type “A”) was promulgated with effect from August 6th and the second (Type “Z”) with effect from October 13th. Both these establishments were compiled from such men as were available at the time, to meet a sudden operational requirement; they represented the urgency of the moment rather than what was required for the work to be done. Members of the “A” Unit took part in the occupation of Leros, Cos and Samos and in the fighting which preceded the loss of those islands. A ‘standard type’ PWE Forward Unit was not finally evolved until the end of the year; the War Establishment was promulgated with effect from December 29th and the formation of two such units authorised with effect from January 6th, 1944. These are the present 814 and 815 Units.

Functions of a PWE Forward Unit

5. A PWE Forward Unit is designed for work with a striking force in the field: it is attached to Force (or Army) HQ and the Unit Commander is a member of the Force (or Army) Commander’s staff. Its principal functions may be defined as follows:-

(a) to give any possible assistance to the Force Commander and forward Unit Commanders in dealing with problems of local politics and local morale and to ensure that such problems do not hamper military operations.

(b) to conduct, on directives from PWE any propaganda to that end among the local civilian population on both sides of the line.

(c) in consultation with the proper military authorities to devise and organise propaganda action, whether by written or other means, with a view to demoralising or misleading the enemy.

(d) to investigate and report back to PWE the state of local and enemy morale and political feeling and to advise on the effect of our long-distance propaganda to the area in question.

(e) to prepare the way for PWE occupational teams in the area in question.

The methods by which these tasks are carried out are outlined under ‘Handling’ below. The tasks themselves may be summarised, in order of importance, as being (i) to help operations by demoralising the enemy and keeping the local population in a favourable frame of mind, (ii) to collect and send back local intelligence for PWE headquarters, (iii) to lay the foundations for subsequent PWE occupational work.

Composition

6. It should be clear from the above that, if the Unit is to work efficiently in a forward area on tasks mainly political but partly military in their nature, its members, and particularly its Commander and his officers must be able to secure the confidence of the Staff and of all Commanders from the Force Commander downward. Naturally, too, there will tend to be a certain amount of suspicion of such unfamiliar ‘extras’ among unit commanders burdened with the responsibilities and anxieties of battle. It is essential therefore, that any PWE Fwd Unit should be organised on Army lines, should be familiar with Army organisation and procedure and, most important of all, should possess at least the minimum of military training expected of their rank and should be able at a pinch to take part in any military operation. In short, both officers and men should be first and foremost soldiers, and not simply experts wearing Khaki as a matter of convenience.

7. Since the Unit may have to serve in a number of different countries with widely different languages and populations, it must be at the same time both flexible and stable – flexible in order to cope with the local population and enemy troops in any part of the Balkan Peninsular, and stable, in order to preserve administrative continuity. This latter point is of particular importance for the non-specialist Other Ranks (clerks, cooks, Despatch Riders, etc.) who remain with the Unit throughout and must have over them throughout officers whom they know and who know them. The Unit is therefore organised in two groups, a HQ group, for command, administration and production, and a group of three Reconnaissance Sections, for forward work and intelligence. The whole consists of 17 officers and 55 Other Ranks.

8. The HQ group consists of 8 officers and 44 Other Ranks and is constituted as follows:-

Command:

Commanding Officer (Lieut-Col) with driver and Jeep.

Second in Command (Major) with driver and Jeep.

Administration:

The War Establishment Committee ruled that the Unit was not to possess an Adjutant as such; the duties of Adjutant have therefore to be discharged either by the 2 i/c or by one of the other HQ officers, probably the QM and TO.

CSM, Orderly Room Sjt, 2 Clerks with 1 3-ton lorry fitted as an office and driver.

4 Orderlies carried on Signals lorry.

Production

Production Officer (Major);

Editorial Officer (Lt) for language of the country;

Editorial Officer (Lt) for enemy language;

Sjt Printer;

2 Compositors;

with 1 15-cwt truck and 1 3-ton lorry carrying the press and type and 1 3-ton lorry carrying stores.

Signals

Signals Officer (Lt) with Jeep and driver.

Signals Sjt with motorcycle.

1 Mech (E/S), 3 Signalmen, 1 Storeman, with 1 3-ton lorry and 1 15-cwt truck driven by driver-operators.

3 Despatch Riders with motorcycles.

The Signals Section is responsible (a) for contact with Force (or Army) Signals, over whose net all communications between HQ and Recce Sections must pass; (b) for the maintenance and repair of all electrical equipment in the Unit (monitoring and other sets, public address systems etc, for the technical upkeep of the monitoring service; and for the operation of any direct link between Unit HQ and PWE Rear HQ when such is established.

Q and Transport

QM and Transport Officer (Captain)

CQMS

Transport Sjt (with motorcycle), 1 Corporal Clerk, 1 Corporal Fitter, 1 Lance Corporal (water and sanitary duties), 3 cooks, 2 storemen, with 2 3-ton lorries (one Q and one transport), one driven by driver-mechanic.

Intelligence

Intelligence Officer (Captain) with Jeep and driver;

Intelligence Sjt;

The Intelligence Officer is responsible for collecting and co-ordinating all information of political warfare interests which reached the Unit from various sources (Recce Sections interrogations; Army and HQ Intelligence, etc.) and for combining this information into a coherent picture on which the Commanding Officer can base his propaganda policy. He may also be charged by the CO with the drafting of Intelligence reports for transmissions back to PWE headquarters.

9. The three Recce Sections each consist of 3 Officers and 4 other ranks (1 Sjt, 1 Cpl, 2 Drivers). The Officers should be conversant either with the language and background of the country (1 Captain, 1 Lt) or with the language and military organisation of the enemy ( 1 Captain).

The functions of the Recce Sections are dealt with below. Each section has a Jeep, a 15-cwt truck and a motorcycle.

Handling

10. The general principles underlying the handling of the Unit are simple and have already been touched on in paragraph 7 above. The HQ group remains at, or near, the HQ of the force to which the Unit is attached. It is responsible for maintaining close liaison with that HQ and with the Force Commander, for regulating propaganda policy throughout the Unit in accordance with the directives received; for devising and controlling political warfare operations within its area in the closest consultation with Force HQ; for the administration, discipline and supply of the Unit; for the Unit monitoring and printing services; for Unit communications; for all intelligence and other reports sent back to PWE headquarters, who have to be kept continuously in the picture; and for political warfare among the local population in their own immediate area.

11. The Recce Sections are the ‘feelers’ of the Unit, and may be used in one of two ways, according to the size of the area covered by the Force, distances between Force HQ and forward troops (which in Italy may not be much above 50 miles, whereas in Tunisia it might be 150 or more), the nature of the country, and so on. Either, if the geographical scale is small, Recce Sections can be held at Unit HQ and dispatched on tasks to various sectors of the front, or they can be definitely attached to some forward HQ, not further back than Division, for work within a specific area. The latter method has the advantage of tying the section more intimately to the local command, with greater familiarity and confidence on both sides: further a Divisional or Brigade Commander is more likely to look with a favourable eye on a unit, which is definitely attached to him, than on one which comes moving into his Area, however unimpeachable its credentials from Force HQ.

12. In whatever area it may be attached or sent to work, a Recce Section is responsible for collecting all available information regarding the local population and the enemy: for advising on, and (subject to the wishes of the Unit Commander) conducting, propaganda to both: for frontline interrogations: and for organising any local contacts with friendly civilians or irregular fighting forces behind the enemy lines.

13. From what has been said above it will be clear that in event of a Unit moving over, for example, from Greece into Yugoslavia, the following personnel might be changed without affecting the identity or continuity of the Unit:- all Recce Section Officers (probably the enemy language Officer might remain) and NCOs (where experts): the local language Editorial Lt and possibly the Intelligence Officer.

British and American Methods

14. It may be useful to give a short comparison between our own and the American methods of organising political warfare in the field. Briefly, an American psychological warfare ‘combat team’ differs from our own conception of a Forward Unit in (a) its civilian component, (b) its greater emphasis on technical equipment, with consequent lesser mobility, (c) its detachment from the Army organisation, and (d) its greater subordination to policy control by Army HQ. All these points of difference interlock and produce an organisation which in a purely British army setting might find itself badly hampered in its work. Taking the above points in order:

(a) Civilians: The original reason for the large number of civilians employed by PWB was the fact that the US Army was in the beginning desperately short of man-power (especially officers) and that the men most obviously suitable for political warfare work were civilians whom it would have meant serious loss of time to put through a military training. Also the Americans did not (and, with certain exceptions, still do not) think of frontline warfare as involving anything more essentially military than broadcasting to the enemy, interrogating prisoners and producing leaflets for the guns to fire – all of which can be done well behind the frontline.

There can be no objection to using civilian technicians at say Army HQ, provided they are suitably garbed so as to comply with international regulations regarding combatants: but it cannot be claimed that it makes for greater respect for the Unit in military circles, even in American military circles which are more tolerant in such matters than our own. Certainly the Army will give a friendly reception to any man who knows his job and is working hard at it, but it cannot be expected to receive him as a soldier or to identify the work he is doing with its own work. This applies more and more, the further one goes.

(b) Equipment and Mobility: American equipment, printing, wireless, transport, is magnificent and no praise is too high for the efficiency of the experts who work and maintain it: but it is for the most part delicate and quite incapable of being moved at speed across bad roads or difficult country. In addition, the more abundant and elaborate the equipment, the greater the number of men (and skilled men) needed to operate and tend it.

I am inclined to say that for frontline purposes, the Americans have become too tied to their machinery and that an equally effective, if less finished, job could be done by fewer men with less equipment. At the moment the Italian front is stagnant; even so the 5th Army Combat Team, with an enormous printing van, are having most of their printing done in Naples. If they had suddenly to move forward, they would be entirely dislocated, and it is precisely during rapid withdrawal that an enemy force is most sensitive to propaganda. If the Combat Team had the equivalent of our Recce Sections i.e. highly mobile units keeping pace with the forward troops, its present elaboration would not matter so much (apart from the increased man-power it required): but it has not, partly because it lacks the men with military training required for frontline work and partly because of its relations with the Army.

(c) Position vis-à-vis of the Army: For a variety of reasons, an American combat team does not form an integral part of the force with which it is working. Its principal officers may be well received at Army HQ (up to a certain level), it may be given all facilities for the shooting of leaflet shells or the interrogation of prisoners, its members, many of them, may be personally well liked, but it is not accepted as a military organisation. The causes of this lie partly in the origin of these teams and in such things as the relations between OWI and the War Department at Washington: partly in Colonel Hazeltine’s own immense influence in Army circles which sufficed to procure for his units all that was needed; partly in a desire to be free from Army dictation; partly in the failure to weld political warfare sufficiently closely into the tactical plan; and partly, as suggested above, in the large participation of civilians in work which the Army will always be slow to accept as military. But, whatever its causes, the effects of this detachment are serious. An attempt to keep psychological warfare independent of Army control, possible while Colonel Hazeltine was there to sponsor it, has on his departure resulted in its falling more completely under that control than is desirable from its own point or indeed than it would have done if it had frankly and willingly placed itself at the Army’s disposal. The most visible result of this state of affairs is a marked reluctance on the part of junior officers to go into any HQ, from Army downwards, except on some particular errand, whereas they should have succeeded in establishing relations which would make them acceptable visitors in any HQ up to Brigades at any hour of the day. In short, the Army has not accepted them as being of itself but as outsiders pursuing their own line of work within the Army area. This has one further and most serious consequence. Not being of the Army the Combat Team has no War Establishment and every item of its military equipment from transport downwards, has to be begged, borrowed or stolen. It is not entitled to any Army issue whatsoever.

(d) Policy: Although it prevents the Unit from contributing all they might to operations, this lack of close contact with the Army might be considered as no more than a pity if the Unit gained thereby some compensating freedom and were allowed to pursue their own course, with the necessary facilities from the Army for shooting leaflets, interrogating prisoners, etc. Actually, as it seems to me, they have the worst of both worlds, since, while they do not have the advantages which close association with the Army would give, they are subject to a strict scrutiny by GHQ of every leaflet which they write, and in matters of propaganda policy they have to submit to a degree of dictation from the staff which we would find intolerable.

15. To sum up, owing largely to the conditions of its birth, the American Combat Team suffers far more than it gains from its nominal independence of the Army. In particular this, and the lack of military personnel, hampers it in the execution of what we would regard as frontline tasks, such as rumour and assistance in tactical deception. At the same time, within the limitations imposed on it, it is doing some magnificent work. Its monitoring and printing services are first-rate, so is its drafting of German propaganda, and its interrogation of prisoners is excellently run, though at the moment understaffed. Largely again owing to lack of man-power and to lack of Italian speakers, less is being done in respect of the local population than might be desired. It is to be hoped that our own unit will be able to help in these respects and, besides gaining frontline experience and learning much regarding the technique of propaganda to the enemy, will help to give the American Unit that mobility in the forward areas which at present it lacks.

Source: TNA FO 898/309. Transcribed by www.psywar.org, 13 March 2017.